(Image: alternativemovieposters.com)

Determinism verses Free Will: The Mythic and Secular Architecture of Minority Report

By Truman Hood

Minority Report is a dystopian warning of a police-state, big brother-esque surveillance society that has experienced a complete destruction of free will. This central idea of the film is told not only through exposition throughout the film, but also by the built environment where the storytelling architecture assists in creating a narrative of a self-fulfilling prophesy. The built environment of Minority Report conveys how humans have abandoned the belief that their fates are determined by greater powers than themselves, such as gods or karma. Instead of mystic powers responsible for the repercussions of those actions, the contemporary worldview shifted. Abandoning this mythic belief in determinism by evolving into a secular belief of free will, Minority Report proposes a future which has reversed this process; humanity in 2054 is confronting a deterministic belief through science and technology. I attempt to understand and explain the struggle of determinism against free will in the film Minority Report space and placemaking through representation in architecture and built environment.

The narrative of Minority Report follows John Anderton, police chief of the Washington DC PreCrime department, who oversees three precognitive telepaths called PreCogs. These PreCogs can predict murders before they are committed, which Anderton and his force are sent out to prevent. However, Anderton soon witnesses a predicted murder where he is the perpetrator. Now accused of an impending pre-meditated murder of a victim he has never heard and of which he has no intention of committing, Anderton escapes and goes on the run to uncover dark secrets about the system he has spent his life creating.

The film begins within a police station that looks more like a sterile laboratory than precinct headquarters, with glass and concrete circular platforms almost floating above curvilinear ramped walkways lined with gleaming stainless-steel rails. The extremely severe and unforgiving nature of the space reflects the stark professionalism and uptight elitism of the main character rigidly striding past the camera, whom we immediately begin following. The protagonist, John Anderton, is a noir character; cold and calculating police chief with is dealing with dark inner demons; addicted to drugs as a coping method to deal with his ruined marriage resulting from the disappearance of his only son, John loses himself in his work when not lost in his depression-inducing drug binges. The blurring between the lines of laboratory and police precinct becomes even murkier when it is revealed that the space also serves as a temple-esque home for Oracle-like prophets of future crimes, called the PreCogs, for their precognitions. This is driven home when several detectives literally use the nickname ‘The Temple’ for the precinct and even state “Come on, Chief, you think about it, the way we work - changing destiny and all - we're more like clergy than cops.” The three PreCogs float in a mostly-tranquil milky or amniotic fluid substance under UV lamp, not unlike a plant in a vegetative state. This futuristic temple is an architectural representation of the mythic, a dogmatic declaration of guilty by a higher power onto humans, similar to the temple of the Oracle who relays determination of fate from the gods to the Greeks.

Figure 1

Believing he has been framed for an impending murder, Anderton must escape this futuristic district of the city. This is the last we truly see of the super futuristic world through the architecture. While the technology and gadgetry continue to impress, from here on out much of the film takes place in a built environment very similar to our contemporary world. Anderton takes refuge in slums similar to those of today, non-sci-fi parks and urban landscapes, slightly mutated from those of present-day. Many of the scenes in the film could have taken place in today’s time, with only a hint of futuristic architecture, technology, or fashion. The juxtaposition of these two extremes prevails throughout the film. The new pristine futurist architecture represents a rejection of the past or suppression of the old built environment, which is representing the architecture of free will.

For example, when Anderton enters the city’s prison, known as the “Department of Containment”, he meets the overseer who is more of a maintenance technician or sentry rather than a warden, who is playing classical music on an organ. While at first seeming odd, it is revealed that the prisoners are kept in an open panopticon rather than cells, held in row after row of individual vertical stasis chambers. The “Department of Containment” appears to the audience more a laboratory than a prison. Detained somewhere between awake and dead and fed with plastic IV drips pure vital nutrients, none of these would-be criminals have committed the crime they were imprisoned for, having been stopped and arrested by Precrime before they could commit the crime. This strange, cold pedestal storage of prisoners is a take on the evolution of the prison that has essentially turned its prisoners into zombies-like dreamers. The overseer’s music now makes more sense in this environment being we all understand that classical music benefits sleepers, but mostly because the entire operation reminds one of a giant church organ with the cylindrical stasis chambers rising tube-like, arrayed in a vast half-circle around the panopticon. In Michael Foucault’s post-structuralist concept of law-enforcement institutions, this Department of Containment - as well as the seemingly pure yet dystopian world of Minority Report as a whole - acts as the futuristic version of the Ship of Fools. Acting initially as a method of punishment and deterrent of crime, the containment has become a part of a political power structure. Anderton’s journey from a part of 2054’s United States society of Self into the Other where he falls from a center of logic, reason, and power into a status of less than human, exemplified when he joins the zombie-like prisoners in the stasis chambers. These designed elements of the built environment demonstrate the power of the regime composed of administration and corporation. In this way the architecture conveys how powerless the individual is against the powers the Anderton supported and now must combat. This example of pristine futuristic architecture is another representation of authority and surveillance, of complete control of space and people through science and technology.

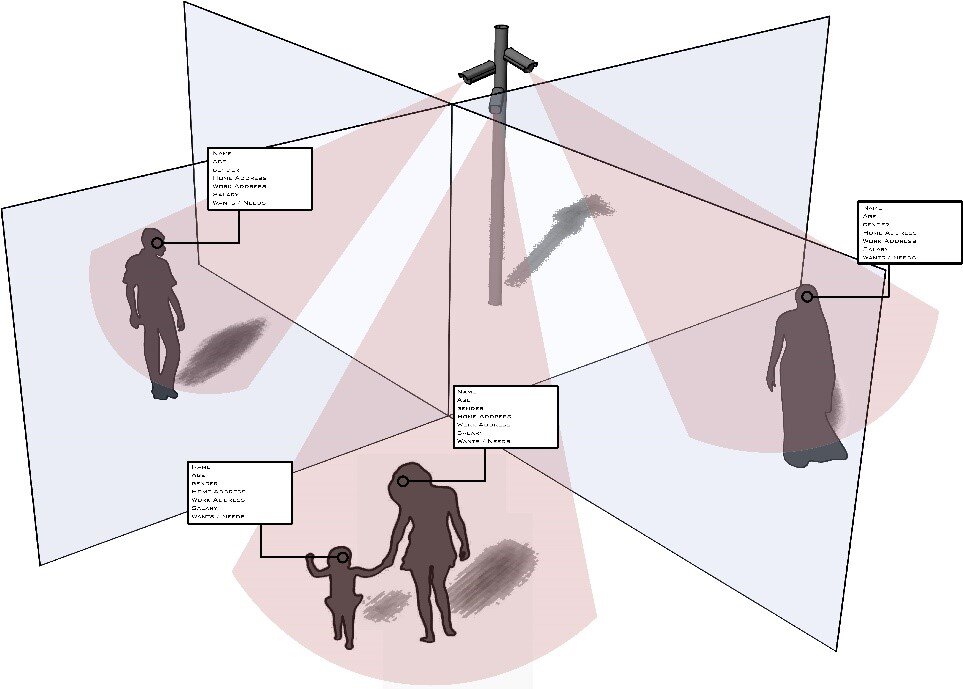

Figure 2

Old and run down architecture, the opposite of pristine futurist design, represents transparency and honesty in the film. This heretical resistance to myth and authority takes place in Later in the film there is a sequence in which a shock trooper PreCrime squad hunts Anderton deep into the slums. Tracking Anderton into a decrepit apartment bloc, the unit deploys hundreds of sleek thin-legged metal spiders that climb from room to room and through walls or floors alike. The resulting scene is a top-down montage that pans the audience around the floorplan through the broken ceiling looking onto the spiders as their mechanical legs pull open the eyelids of citizens in order to scan their retinas for identification. Eerily reminiscent of the set for Dogville, the audience gets an uninterrupted view into a snippet of daily life of the different archetypical near-hovel dwellers, interrupted briefly by the spiders then just as quickly returning to their unassuming and unmonitored lives in poverty. Not only is this scene a marvel of cinematography, but it also relies on the architecture to tell the story rather than utilizing expositional dialog. This method of storytelling balances futuristic tech of the inhabitants, spider drones, and the all too familiar tenement bloc to express onto viewers the tension as we race along with the hunting spiders towards our hiding protagonist. This setting is juxtaposed against the prosperous parts of the city that are saturated with shopping, augmented reality, and surveillance. However, the predatory eye scanners are still prevalent in the form of cameras which tailor the adverts exactly to the individual, calling out their name in liberal real-life product placement in the film. This reflection of our contemporary-day online retail tracking panopticon is ham-fisted, but not too far of an exaggeration of the invasive trend we see today.

Throughout the film, the representation of free will and determinism is also expressed through symbolism of the eye. Early in the film, an eye-less drug peddler foreshadows: “in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king”. The corporate surveillance and especially future-witnessing precogs represent a mythic all-seeing eye. Having this kind of knowledge or insight that no one else has or is blind to represents power in the extreme. The public reside in the land of the blind, where people are ultimately unaware they are being constantly surveilled. Thus, the masses can be controlled by those in the know, those in power. This surveillance is executed in Minority Report through seeing the future a la PreCogs, but also through retinal-scanning cameras, mechanical retinal-scanning spider drones, etc. Escape from determinism to freedom and free will is a significant motion in the film through literal removal and replacement of one’s eyes; both the drug dealer and Anderton physically remove theirs. The architecture of authority in Minority Report, where surveillance takes place, is pristine: shiny, new, and clean. Transparency is paramount, with heavy use glass demonstrating no privacy whatsoever.

Architecture of freedom is often old, decrepit, falling apart, dirty, and most importantly neglected. However, opaqueness is celebrated as privacy and freedom, authenticity which can only be found in neglected spaces. Just as the personal freedoms and individual rights are neglected by authority and apathetic public.

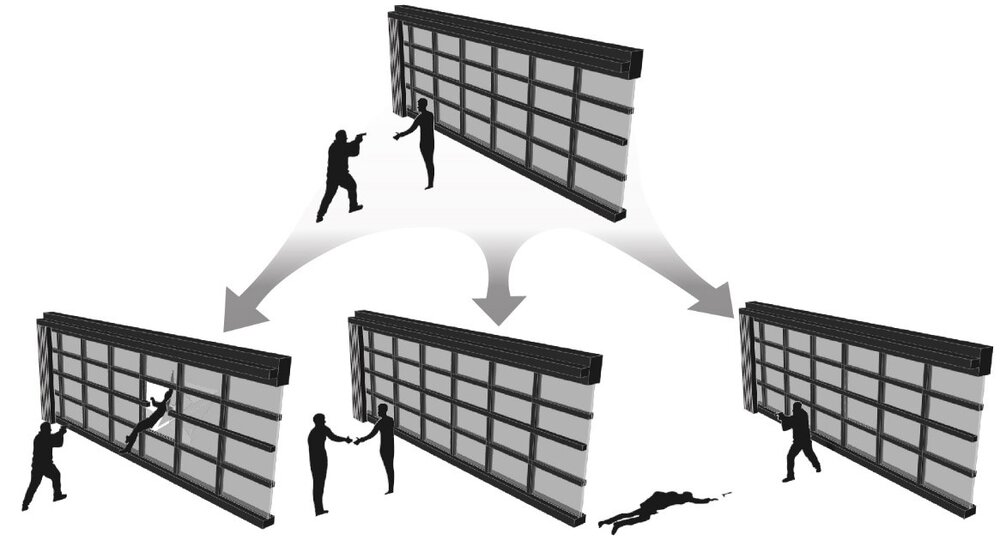

Figure 3

We are immediately witness to one of the film’s futuristic feature moments, with Anderton interacting with his enormous computer screen. In order to operate at his transparent standing desk, Anderton must conduct almost dance-like calisthenic motions in shear and precise jerks. In the first crime we witness PreCrime solving, Anderton uses the architectural features of house to attempt to locate a prophesized origin of a crime: “Original running bond brick pattern, streamlined early Georgian details… The brick has been repointed, the glass is original with new glazing bars. I show composite moldings with dentils. Someone took care in the renovation. Let's find the architect...” Utilizing this information, the police are able to identify the architect: “I show a match for Dwight Kingsley. Nineteenth century architect. He did two dozen houses in D.C...” Exiting the interior of the station, one would be forgiven for thinking this was set in our modern-day. The exterior of the Future Crimes Department is very much nondescript compared to our current-day institutional police buildings, albeit a prosperous one. Arriving at a residential Georgetown neighborhood with green parks and rowhouses, the familiar and almost mundane design of the neighborhoods contrast harshly with the mega highways and gigantic skyscrapers and vast infrastructure of the city centers. This suburban neighborhood is curiously unchanged compared to the futuristic city center. This mythical semi-past of the perfect American townhouse row reminiscent of a 50s wealthier class home.

After preventing the crime and capturing the potential perpetrator, Anderton returns to his flat. Anderton’s home is a stylish organizational composition of large pods, big screen television displays, and a swirling acrylic mount for his car which enters sideways directly from the street-façade. All these elements making up his condominium-like house come together to scream a combination of digital- and even space-age residence style, reminiscent to a live-action gritty Jetsons home. Upon entering, Anderton utilizes a voice recognition similar to Alexa smart-home technology of the late 2010s predicted in 2001. Simply stating “I’m home.” results in a reaction from the intelligent architecture itself; the lights turn on and music plays. The architecture of Anderton’s flat contrasts greatly to ever other residence we see for the rest of the film and one example where the film fluctuates from obviously futuristic to the more recognizable or semi-familiar contemporary style of most of the places we pass through after.

The constant and invasive surveillance warned by Foucault is expressed throughout the film’s built environment in many ways. From commercialist advert retinal-scanners in every public space to horrifying spider drones and all-knowing psychics. Minority Report takes Foucault’s panopticonism to the extreme where the only refuge that can be found is located either in the deepest bowls of the seedy old city or through a complete exodus from metropolitan areas. The daily life of a citizen in any urban center is to star in their very own Truman Show-esque play, where everything they do physically and digitally is surveyed and recorded, only to be immediately reflected in the form of highly-personalized advertisements. This architecture is also acting as a near PreCrime, where any crime committed is surly to be seen by one of any hundred black beady eyes following the public’s every move from a camera or retinal scanner. At this extreme level of heightened surveillance, is there even a need of precogs? The only sacrifice for a perfectly peaceful and safe American society is to merely give up any human right to privacy to the built environment. In the futuristic neo-noir Minority Report, the constant surveillance for consumers and marketing for advertainments truly represents an invasive police state monitoring its populace. As a society oversaturated in identification and consumerism, the non-authenticity is made more evident by the attempt at personalized marketing yet so obviously proving itself intrinsically impersonalized .

References

Abuhela, I. "Significance of Future Architecture in Science Fiction Films." In First Architecture and Urban Planning Conference. 2005.

Best, Steven, and Kellner, Douglas. “The Apocalyptic Vision of Philip K. Dick.” Cultural Studies, Critical Methodologies. 3, no. 2 (2003): 186–202.

Cooper, MG. “The Contradictions Of "Minority Report".” Film Criticism. 28, no. 2 (2003).

Moeny, Jordan. "Things You Wouldn’t Believe: Predicting (and Shaping) the Future in Blade Runner and Minority Report." a journal of communication, culture & technology (2019): 47-57.

Picon, Antoine. "Architecture and the Virtual." Thesis, Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, (2003)

Rossi, Umberto. "A Sort of Homecoming: Architecture and SF." Science Fiction Studies 39, no. 1 (2012): 112-17.

Spielberg, Steven, Molen, Gerald R., Curtis, Bonnie, Parkes, Walter F., Bont, Jan de, Frank, Scott, Cohen, Jon, et al. Minority Report. United States]: DreamWorks Home Entertainment: Distributed by Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 2003.

Wąs, Cezary. "The Tannhäuser Gate. Architecture in science fiction films of the second half of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century as a component of utopian and dystopian projections of the future." University of Wrocław (2018).

Wright, David. “Alternative Futures: AmI Scenarios and Minority Report.” Futures. 40, no. 5 (2008): 473–88.

from REVIEW BLOG - Every Movie Has a Lesson https://ift.tt/2RXiIeu

No comments:

Post a Comment